📝 Introduction

Procurement in the construction industry has evolved far beyond the traditional tender-and-build model. Today’s infrastructure projects—especially under frameworks like the Private Finance Initiative (PFI)—demand sophisticated planning, collaborative delivery, and dynamic risk management. In this multi-part blog post, we explore seven essential dimensions of modern construction procurement. From the historical context that gave rise to innovative models like Design and Build and Construction Management, to the critical role of clients as active stakeholders, and all the way to estimating strategies, submission planning, and lifecycle cost management, this guide offers a detailed look into how projects are successfully procured, delivered, and sustained in today’s complex environment. Whether you’re a contractor, consultant, or client, these insights will help you better understand how to navigate and lead in the construction procurement process.

Evolution of Construction Procurement Strategies:

Modernizing Procurement Methods in Construction: From Banwell to Best Practices

The procurement landscape in the construction industry has undergone significant transformation over the past several decades. What was once a rigid, fragmented process has gradually evolved into a more integrated, flexible, and client-focused system. This shift was largely catalyzed by critical industry reports such as the Banwell Report (1964) and Latham Report (1994), which identified chronic inefficiencies, conflict-driven relationships, and disjointed project structures as core obstacles to successful construction delivery.

The Traditional Model: Fragmented and Adversarial

Traditionally, construction procurement followed a sequential and segmented path. Clients would appoint a consultant—usually an architect or engineer—to lead the design. A quantity surveyor would later step in to prepare bills of quantities, monitor financials, and manage bids. The contractor entered the scene much later, after the design was finalized, with minimal early input. This linear process separated design from construction and bred adversarial relationships, particularly between designers and contractors.

The Banwell Report was among the first to call out the rigidity of such arrangements. It argued that the industry’s “contractual and professional conventions” were outdated and incompatible with the modernization needed for economic and efficient project delivery. The report advocated for experimentation with new systems that promoted better coordination, collaboration, and flexibility across the project lifecycle.

The Latham Report and the Call for Reform

Three decades later, the Latham Report: Constructing the Team (1994) echoed and amplified Banwell’s concerns. Sir Michael Latham strongly criticized the industry’s adversarial culture and called for radical change, including collaborative contracting and integrated project delivery. He championed the use of new forms of contract—such as the New Engineering Contract (NEC)—to foster a spirit of “mutual trust and cooperation.”

Latham’s vision became a turning point, leading to a broader acceptance of procurement methods that aligned design and construction efforts more closely. His work encouraged the industry to adopt approaches that emphasized joint responsibility, early contractor involvement, and shared risk management.

Emergence of Modern Procurement Methods

In response to these calls for reform, several new procurement methods gained traction:

- Design and Build (D&B): Under this model, a single entity is responsible for both design and construction. This method reduces fragmentation by offering a single point of accountability. It improves buildability, shortens timelines, and enhances cost certainty. However, it also shifts design control away from the client, which can impact quality or aesthetics if not carefully managed.

- Management Contracting: Popularized during the 1980s for large, complex projects, this method introduces a management contractor early in the project. They work alongside the design team to contribute construction expertise and later manage the execution through subcontracted work packages. This approach allows early starts on site and adaptability during design development but offers less cost certainty.

- Construction Management (CM): In this method, the client appoints a construction manager who oversees the work of multiple trade contractors. It offers maximum client control and transparency, but also demands a high level of involvement and expertise from the client side. CM is favored in dynamic, fast-track environments where change is expected throughout the build process.

A Shift Toward Integration and Collaboration

The evolution of procurement reflects a broader industry trend: moving away from isolated silos toward integrated team structures. Clients are no longer passive participants—they are active contributors to project planning, design, and execution. In many cases, project success hinges on early and continuous collaboration between all stakeholders.

These modern procurement routes enable faster delivery, more predictable budgets, and a reduction in contractual disputes. While each method has its trade-offs, they all aim to overcome the historical shortcomings of traditional contracting models.

Conclusion

From Banwell’s early observations to Latham’s formal recommendations, the construction industry has gradually embraced procurement models that prioritize flexibility, integration, and collaboration. The journey toward modernization is ongoing, but the adoption of design and build, management contracting, and construction management signals a decisive break from the adversarial traditions of the past.

Why Client-Centric Procurement Matters in Modern Projects

Client-Centric Procurement in Construction: A Shift Toward Active Ownership

In recent decades, the role of clients in the construction industry has transformed from passive bystanders to active participants shaping project outcomes. Once viewed primarily as financiers and recipients of completed works, clients are now increasingly recognized as integral members of the construction team. This shift toward client-centric procurement reflects broader changes in industry expectations, delivery models, and collaborative strategies aimed at improving efficiency, accountability, and long-term value.

From Passive Payers to Project Stakeholders

Historically, standard contracts placed limited obligations on clients. Their main responsibilities involved appointing a design team, granting site access, and making timely payments for completed work. However, this narrow role often led to misaligned expectations, communication gaps, and adversarial relationships among contractors, consultants, and clients.

The industry’s pivot began in part due to mounting criticism over delays, cost overruns, and design deficiencies. In response, clients—especially those managing large-scale or repeated developments—began seeking greater control over outcomes by engaging more actively in project definition, design, procurement, and delivery.

Today, clients are expected to be proactive in shaping their projects. This involves:

- Defining spatial needs: such as production capacity, accommodation, or public access;

- Making strategic investments: to exploit new market opportunities or meet compliance standards;

- Asserting identity: by enhancing brand presence or aligning facilities with corporate or civic values;

- Selecting strategic locations: to optimize logistics, customer reach, or public service delivery;

- Navigating political and regulatory landscapes: especially within public infrastructure initiatives.

This expanded role requires clients to possess, or acquire, a deeper understanding of construction processes and the implications of various procurement strategies.

Controlling Design, Time, and Cost

Clients have realized that early and continuous involvement is key to minimizing risks and maximizing project value. In the modern procurement environment, clients can:

- Control design by participating in early-stage planning, defining design briefs, and ensuring alignment with operational goals.

- Manage timelines by fostering faster decision-making, monitoring milestones, and streamlining approval processes.

- Influence cost certainty by implementing value engineering, improving tender documentation, and managing scope changes collaboratively.

As the document emphasizes, “clients aim to appoint a team which they can trust and rely on to reduce uncertainties during a building’s design, construction and use.” This trust-based environment supports a shift from transactional to partnership-based engagements, where mutual goals are shared by all parties.

Public Sector Leadership: PFI and Prime Contracting

The shift toward client-centric procurement is especially evident in the public sector, where governmental bodies and agencies have pioneered innovative contracting frameworks. Two such models are the Private Finance Initiative (PFI) and Prime Contracting.

Under the PFI model, private sector consortia finance, design, build, and operate public infrastructure—often over a 30-year concession period—while the public client pays a performance-based fee known as a unitary payment. This model enables public authorities to maintain strategic control over services while transferring certain operational and financial risks to the private partner.

PFI projects emphasize:

- Clearly defined output specifications rather than rigid design briefs;

- Long-term service level agreements monitored by the client;

- Full lifecycle cost planning and risk management.

In a similar vein, Prime Contracting shifts the client’s role toward strategic oversight rather than day-to-day involvement. A single Prime Contractor is appointed to manage all subcontracts, design coordination, and delivery, allowing the client to focus on performance metrics and value for money.

These public sector models have inspired private sector clients to adopt similar approaches, especially where long-term asset performance and lifecycle efficiency are priorities.

Conclusion

Client-centric procurement has redefined how construction projects are planned, delivered, and measured. By taking an active role in defining objectives and managing risk, today’s clients help foster alignment across all stages of project execution. Whether through integrated partnerships or performance-based contracts like PFI, the modern client is no longer a passive observer but a strategic force shaping the future of the built environment.

Comparing Construction Procurement Strategies and Risk Profiles

Understanding Procurement Systems and Their Risk Profiles in Construction Projects

In the ever-evolving construction industry, selecting the right procurement system is crucial for achieving successful project delivery. The procurement method not only dictates how responsibilities are allocated among the project participants but also shapes how risks—financial, design, and executional—are distributed. The document under review provides a clear breakdown of the four major procurement systems commonly used in modern construction, along with a detailed analysis of their respective risk profiles.

The Traditional Procurement System

The traditional method remains one of the most commonly used procurement models, particularly in the UK. Under this sequential approach, the client hires designers and quantity surveyors first, completes a full design, and then appoints a contractor through a tendering process. The contractor is only involved after the design has been finalized and is not typically responsible for it.

This method emphasizes clear separation between design and construction, allowing the client to maintain full control over the design. It is structured around well-established standard contracts like the JCT Standard Form of Building Contract and the ICE Form for civil engineering works.

Risk Profile:

- Design risk: fully retained by the client and their consultants.

- Construction risk: borne by the contractor.

- Cost risk: moderate, depending on the completeness and quality of design documentation.

- Time risk: can be high if late design changes occur, leading to variations and disputes.

Design and Build (D&B)

The design and build system addresses many shortcomings of traditional procurement by integrating both design and construction responsibilities under one entity—the contractor. This offers the client a single point of responsibility and has grown in popularity due to its advantages in time and cost certainty.

The design team may be in-house or commissioned by the contractor. In some cases, clients “novate” their existing designers to the contractor, which can lead to tension if the team’s loyalties shift mid-project.

Risk Profile:

- Design risk: transferred to the contractor.

- Construction risk: borne by the contractor.

- Cost risk: lower due to fixed lump-sum contracts.

- Quality/design integrity risk: higher, as contractors may prioritize cost over aesthetics or longevity.

Clients benefit from overlapping design and construction phases, which shortens the project timeline, but they must be vigilant to ensure design quality meets expectations.

Management Contracting

Management contracting introduces the contractor at an early stage—not to perform construction directly, but to manage and coordinate packages executed by specialist subcontractors. The contractor works closely with the professional team to contribute to the design process and later administers contracts with the individual trades.

This approach is ideal for large, complex projects where fast-tracking and flexibility are important. It allows for early starts on site before full design completion.

Risk Profile:

- Design risk: primarily with the client and consultants.

- Construction risk: shared; contractor manages but does not execute.

- Cost risk: higher due to open-ended nature; client pays prime cost + management fee.

- Time risk: moderate; construction can proceed before design is complete, but coordination is crucial.

This system is less common today due to lower profit margins and increased pressure on subcontractors, though it remains effective in specific scenarios.

Construction Management

Construction management (CM) is the most hands-on model for clients. Here, the client contracts directly with all trade contractors, while a construction manager—acting as a professional consultant—coordinates the construction process without taking on financial responsibility for delays or cost overruns.

Used widely in the United States and by large property developers in the UK, CM is especially suited to fast-paced environments with rapidly evolving technologies or changing needs. The client has full visibility and control over procurement and execution but also bears the greatest exposure to risk.

Risk Profile:

- Design risk: with the client and design team.

- Construction risk: with the client, as they hold all trade contracts.

- Cost risk: high; no fixed price, relies on precise cost control and expert management.

- Time risk: mitigated through overlapping design and construction stages, but heavily dependent on coordination and decision-making speed.

Comparative Risk Analysis

The document’s Figure 2.1 offers a useful visual summary of risk distribution across contract types:

| Contract Type | Client Risk | Contractor Risk |

| Lump-Sum (Traditional) | Moderate | Moderate |

| Design & Build | Low | High |

| Cost Plus | High | Low |

| Schedule of Rates | High | Moderate |

- Lump-sum contracts provide balanced risk sharing when design documents are complete and accurate.

- Schedule of rates contracts are problematic: the contractor cannot estimate overheads reliably, and the client doesn’t know the final cost until completion.

- Cost-reimbursement (Cost-plus) contracts allow fast starts but offer little incentive to save time or money, shifting nearly all cost risk to the client.

Conclusion

There is no one-size-fits-all approach in procurement. Each method offers a distinct balance of control, flexibility, and risk exposure. The decision ultimately depends on the project complexity, client expertise, design maturity, funding model, and time constraints.

Clients must evaluate their own capabilities and appetite for risk before selecting a procurement route. By understanding the nuances and implications of each system, stakeholders can make informed decisions that support smoother delivery, better collaboration, and successful outcomes.

How Partnering Strengthens Construction Procurement Strategies

Partnering & Collaboration in Construction: Beyond Contracts Toward Common Goals

By the 1990s, the construction industry had developed a reputation for adversarial relationships, costly disputes, and a lack of communication between key players. Delays, finger-pointing, and litigation were often the norm rather than the exception. In response to this fragmented environment, the concept of partnering emerged—not as a new contract type, but as a collaborative philosophy aimed at promoting trust, reducing conflict, and improving project outcomes.

Today, partnering and collaboration are central to many procurement strategies. They are designed to align stakeholders around shared objectives, build long-term relationships, and drive mutual value. However, as the document insightfully highlights, the success of partnering depends not on contractual language, but on the spirit in which it is applied.

The Rise of Partnering: A Cure for Conflict

The movement toward partnering began as a reaction to what the industry had become. The Constructing the Team report by Sir Michael Latham in 1994 played a pivotal role in advocating for cultural reform. He urged the industry to move away from confrontational practices and instead embrace “mutual trust and cooperation.”

Contract models like the New Engineering Contract (NEC) were early adopters of this philosophy. NEC introduced core clauses that required all parties—clients, contractors, subcontractors, and consultants—to act in a spirit of mutual trust. The goal wasn’t just to complete a project, but to achieve a “win-win” outcome where success was shared rather than won at the expense of others.

What Is Partnering in Practice?

Partnering can take several forms. In its simplest version, it might involve a verbal or informal agreement to collaborate in good faith. In more formalized settings, partnering arrangements include:

- Agreed project objectives

- Joint problem-solving frameworks

- Open-book cost transparency

- Performance measurement and continuous improvement

- Shared risk and reward mechanisms

Crucially, partnering does not replace the contract—it complements it. The legal framework remains intact, but the mindset shifts from adversarial enforcement to cooperative delivery.

The document provides examples where partnering has worked well. Contractors offer innovative, alternative bids based on cost savings, shared resources, and joint responsibility. These approaches have enabled teams to eliminate unnecessary claims, reduce overheads, and ensure projects are delivered on time and within budget.

The Limits of “Prescriptive Partnering”

Despite its benefits, the document wisely cautions against “prescriptive partnering.” That is, creating contracts filled with clauses that try to enforce cooperation mechanically. Trust cannot be mandated—it must be earned and demonstrated through action.

For example, simply adding a clause that says “we agree to cooperate” does not ensure collaboration when unexpected problems arise. In reality, stakeholders may revert to defensive behaviors if their incentives aren’t truly aligned or if trust was never built during the pre-contract phase.

Moreover, the text observes that contractors sometimes use partnering language strategically, especially in competitive bids. It’s not uncommon to see proposals filled with phrases like “joint problem-solving,” “value engineering,” or “open-book pricing” that sound collaborative but are tactically designed to enhance the appeal of the bid, rather than reflect actual intent.

This creates a disconnect between the language of collaboration and the reality of delivery, leading to disappointment and, ironically, the very disputes partnering was meant to avoid.

Real Partnering: What Makes It Work?

For partnering to be successful, the construction team must embrace certain principles from the outset:

- Early involvement of all key stakeholders, including designers, contractors, and end users

- Transparent communication about expectations, risks, and constraints

- Clear governance structures that support joint decision-making

- Aligned incentives where parties share the pain of failure and the reward of success

- Commitment from leadership on all sides to uphold the collaborative culture

The most effective partnerships are those where reputational and relational capital matter just as much as financial outcomes. Repeat business, joint ventures, and long-term collaboration are the true rewards of authentic partnering.

Conclusion: Building Trust Beyond the Contract

Partnering is more than a contractual checkbox—it is a mindset. When genuine, it fosters innovation, mitigates risk, and promotes sustainability in construction delivery. As the document wisely notes, however, it must be based on action, not just wording. Contracts can support trust, but they cannot create it.

In an industry still recovering from decades of fragmentation, partnering offers a path forward—not just to build better buildings, but to build better relationships. By focusing on shared goals, honest communication, and mutual benefit, construction teams can transform how they work and how they win—together.

What Makes the Private Finance Initiative a Powerful Procurement Strategy

Private Finance Initiative (PFI) Explained: Redefining Public Infrastructure Delivery

The Private Finance Initiative (PFI) represents a significant shift in how public infrastructure is developed, financed, and managed. Introduced in the United Kingdom in the early 1990s, PFI was designed to harness private sector expertise and funding for the benefit of public services. Through this model, essential public infrastructure—from hospitals and schools to roads and utilities—is delivered and operated by private consortia, while the public sector pays for its use over a long-term concession, typically thirty years.

This comprehensive procurement method has not only transformed the public sector’s approach to capital investment but also brought both opportunities and challenges related to value for money, risk allocation, and contract complexity.

The DBFO Model: Design, Build, Finance, Operate

At its core, PFI adopts a DBFO approach, in which a private consortium—usually structured as a Special Purpose Vehicle (SPV)—takes on the responsibility to design, build, finance, and operate public infrastructure projects.

The public authority, known as the awarding authority, does not pay for the asset upfront. Instead, it commits to making regular, performance-based payments—called unitary payments—over the life of the concession. These payments cover construction costs, financing, maintenance, and operational services, effectively spreading public expenditure over time and tying payment to performance standards.

This structure allows governments to deliver high-quality facilities without immediate capital outlay, while benefiting from private sector efficiency and innovation.

Key PFI Documents and Procurement Process

The PFI process is methodical and document-heavy, ensuring rigorous planning and accountability. The key steps are:

- Needs Identification: The client defines the operational requirements (e.g., number of beds for a hospital, number of students for a school).

- Market Engagement: Private sector firms are invited to express interest in delivering the project on a Public-Private Partnership (PPP) basis.

- Shortlisting & Tendering:

- The Invitation to Negotiate (ITN) is issued to shortlisted bidders.

- Bidders provide designs, pricing, and detailed proposals.

- Preferred Bidder Selection: Based on value for money, not just lowest price.

- Financial Close & Construction: The selected consortium finances and builds the asset.

- Service Delivery: The private party operates and maintains the facility for the agreed term.

- Handover: At the end of the concession, the facility typically reverts to public ownership.

Supporting this process are vital documents:

- Output Specifications: Define service requirements in non-prescriptive terms.

- PSC (Public Sector Comparator): A benchmark showing the cost of delivering the same project using traditional procurement.

- Service Level Agreements (SLAs): Detail the performance standards and monitoring mechanisms.

Benefits of PFI

PFI was widely adopted due to its perceived benefits, many of which have been supported by independent reviews:

- On-Time and On-Budget Delivery: According to the UK’s National Audit Office, 89% of PFI projects were delivered on time or early and within public sector budgets.

- Whole-Life Costing: Since the private sector is responsible for long-term maintenance, there’s a built-in incentive to ensure durable, high-quality construction.

- Asset Optimization: Facilities can generate revenue through shared use or commercial activities, enhancing value for money.

- Integrated Services: Bundling design, construction, financing, and operation creates a streamlined delivery process.

In many cases, PFI helped overcome delays and budget overruns that plagued traditional procurement models, particularly in large-scale, capital-intensive projects.

Risk Allocation in PFI Projects

One of the defining features of PFI is its focus on allocating risks to the parties best able to manage them. However, this must be done carefully and fairly to ensure project success. Key risks include:

- Construction Risk: Transferred to the private sector, which is incentivized to deliver efficiently.

- Demand Risk: Applies to facilities like toll roads, where revenue depends on usage.

- Maintenance & Lifecycle Risk: The private sector is responsible for ongoing performance, reducing long-term costs for the public client.

- Financing Risk: Private partners bear the burden of securing and repaying capital.

- Regulatory and Legal Risks: Shared depending on the nature of the project.

Effective risk transfer is a hallmark of successful PFI projects, but if poorly structured, it can lead to disputes, renegotiations, or financial losses.

Cost Structure and Market Testing

The typical cost breakdown for a PFI contract is:

- 30% Construction

- 10% Maintenance

- 50% Services

- 10% Financing and Management

To ensure competitive pricing, benchmarking and market testing are conducted at intervals during the concession period. These procedures confirm that the quality and cost of services remain aligned with market standards.Common Questions and Public Debate

PFI has not been without controversy. Critics argue that long-term costs can be higher and that some contracts limit public flexibility. However, defenders highlight improved delivery outcomes and better asset management. The key lies in how well the contracts are structured and managed over time.

Questions such as “Are all risks transferred to the private sector?” or “Is value for money truly achieved?” continue to fuel policy debates, but overall, PFI has provided a workable framework for public infrastructure delivery in capital-constrained environments.

Conclusion: PFI as a Strategic Procurement Tool

PFI is more than just a financing model—it is a strategic procurement method that reshapes the relationship between public and private sectors. When properly designed and managed, it can deliver durable, high-performing infrastructure, enhance service delivery, and provide long-term value to taxpayers.

As governments seek innovative ways to fund public services amid fiscal pressures, the principles of PFI—risk-sharing, lifecycle planning, and integrated delivery—will continue to influence the future of public procurement worldwide.

Estimating Strategies in Complex Construction Procurement Projects

Estimating Strategies in PFI Projects: Planning for Precision and Performance

In the world of construction procurement, few models rival the Private Finance Initiative (PFI) in complexity and scope. Unlike traditional procurement routes that rely on fixed drawings and bills of quantities, PFI projects evolve over extended bidding periods, requiring a more flexible and dynamic approach to cost estimation. Accurate and strategic cost planning becomes essential—not just to win the bid, but to ensure the long-term viability and profitability of the project.

PFI procurement hinges on the design, build, finance, and operation (DBFO) model, in which private consortia commit to delivering and maintaining public infrastructure, often over thirty-year concession periods. As a result, estimating in PFI ventures is not limited to construction costs alone; it must also account for lifecycle performance, operational costs, and long-term risk exposure.

Traditional Estimating vs. PFI Realities

In conventional construction contracts, bills of quantities (BoQ) provide the cornerstone of pricing. They offer a detailed, itemized breakdown of work based on finalized designs. However, PFI projects are rarely this straightforward. The bidding process typically spans more than a year, with the design evolving in tandem with financial modeling and client negotiations. This ongoing development renders traditional BoQs impractical.

Instead, PFI projects rely on cost planning strategies that are iterative, flexible, and grounded in benchmarks rather than finalized quantities. The key estimating tool used throughout the PFI lifecycle is the elemental cost plan, which organizes cost data by functional building elements (e.g., substructure, superstructure, internal finishes, services, external works).

Multi-Stage Estimating Approach

Cost estimating in PFI projects occurs over several stages, each aligned with the procurement milestones:

- Pre-Qualification (PQ) Stage

- At this early filtering stage, estimates are broad and rely on single rate metrics, such as cost per square meter or per unit of accommodation.

- Bidders are evaluated on experience, capacity, and general affordability assumptions.

- Preliminary Invitation to Tender (PITN)

- The estimate advances to a short elemental cost plan, often covering high-level breakdowns like GIFA (Gross Internal Floor Area), site development, and provisional allowances.

- Cost planners begin incorporating historical data and benchmarking to guide projections.

- Final Invitation to Tender (FITN)

- The estimate becomes more detailed, with cost consultants providing a fully developed elemental plan based on evolved design drawings and refined specifications.

- Trade contractor input is sometimes introduced here as part of first-stage procurement.

- Inflation allowances and market testing begin to shape financial assumptions.

- Preferred Bidder (PB) Stage

- At this point, estimators deliver life-cycle cost models, factoring in long-term operations, maintenance, and capital replacement schedules.

- The cost plan must align perfectly with the financial model, reflecting risk allocations, unitary payment structures, and long-term cash flow forecasts.

A Hospital Project Case Study: Pricing Strategy Example

The file presents a comprehensive pricing strategy for a PFI hospital scheme, developed during the PITN/FITN stages. This strategy includes:

- Setting a Budget Target

- The consortium sets an affordability ceiling (e.g., £180 million) based on early negotiations with the client’s finance team.

- Using a benchmark rate (e.g., £2,750/m²), a target GIFA (e.g., 65,500 m²) is derived.

- Departmental Area Breakdown

- GIFA is distributed across functional categories:

- Departmental Gross Area

- Communication Spaces (e.g., corridors)

- Plant Areas (e.g., MEP systems)

- For instance: 14% may be allocated to communication zones, and 11% to plant.

- Accommodation Schedule Review

- The estimator works with healthcare planners to confirm spatial allocation per department.

- Discrepancies are flagged early, and strategies are developed to close the gap between drawn area and affordability.

- Cost Planning

- A first-pass cost plan is developed for the financial model, including:

- Building shell and core

- Equipment

- Site infrastructure

- Contingencies for abnormal conditions

- Risk and inflation markups

- Lifecycle Costing

- Cost estimates account for capital replacement, routine maintenance, and asset renewal over the thirty-year term.

- This data is translated into cashflow forecasts and submitted within the formal bid documents.

Submission Documentation and Coordination

Preparing the cost submission is a monumental task. The article emphasizes the need to:

- Start early and assign a senior “presentation manager.”

- Coordinate inputs across the design team, cost consultants, and financial advisors.

- Use both electronic and hard copy formats (often 30–40 copies).

- Ensure consistency between cost plans and architectural drawings.

Conclusion: Estimating for Certainty in an Uncertain Process

Estimating in PFI projects is a strategic discipline, blending technical precision with commercial foresight. It requires layered cost planning, market intelligence, and lifecycle thinking—far beyond the limits of traditional tendering.

As public sector clients continue to demand value for money and long-term service reliability, the role of expert estimators in PFI schemes has never been more crucial. Their work underpins not only the competitiveness of the bid but the sustainability of the entire concession—from day one to year thirty.

Coordinating Submission Documents in Construction Procurement

Submission Documents and Presentation in PFI Projects: Strategy, Structure, and Precision

In Private Finance Initiative (PFI) procurement, success is not just about pricing accurately—it’s also about presenting that price professionally, credibly, and persuasively. The quality of submission documents and the coordination of the bid team can determine whether a contractor moves from shortlisting to selection as the preferred bidder.

Because PFI projects often extend over long timelines and involve large volumes of data, the submission process must be carefully structured and meticulously executed. A strong, well-coordinated submission demonstrates not only the contractor’s technical and financial capability, but also their ability to manage complex, long-term public infrastructure partnerships.

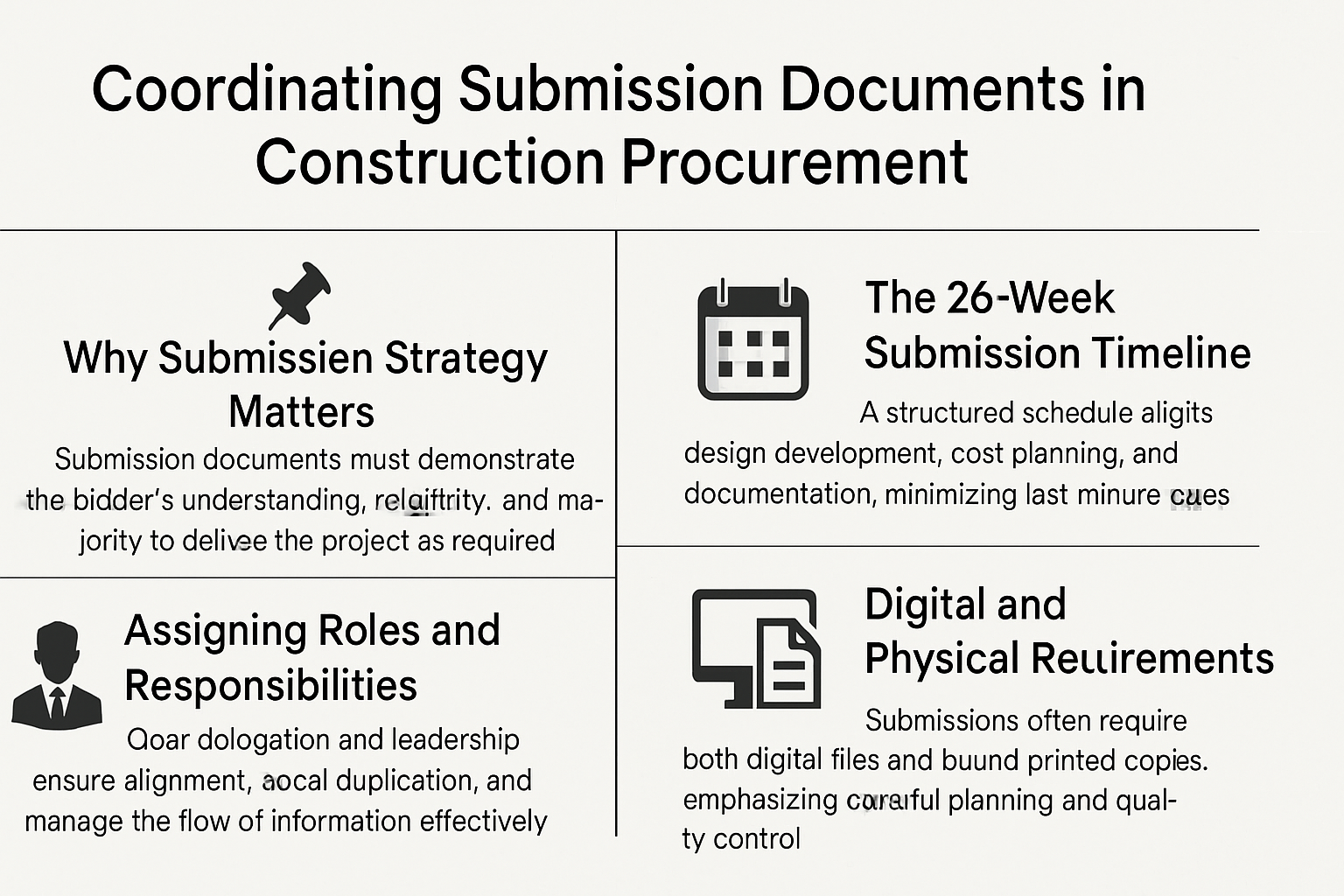

Why Submission Strategy Matters

PFI submission documents do more than respond to tender requirements—they tell a story. That story must show that the bidder:

- Understands the client’s operational needs

- Can deliver the project on time and within budget

- Has accounted for long-term lifecycle performance

- Will act as a trustworthy and capable long-term partner

To achieve this, the bid must be:

- Well-timed: Begin early to accommodate design changes, cost plan iterations, and multiple internal reviews.

- Collaborative: Everyone involved—designers, estimators, cost planners, and finance teams—must understand their roles and contributions.

- Consistent: Submission documents must align across technical, financial, and visual content.

The 26-Week Submission Timeline

The file provides a detailed 26-week submission schedule, outlining key milestones and deliverables for a typical PFI bid (e.g., a hospital project). This timeline offers a practical roadmap to align design development, cost planning, and documentation:

| Week | Key Activities |

| 1–3 | Issue ITN documents, set affordability targets, and develop early floor area benchmarks (e.g., GIFA) |

| 3–5 | Determine new-build vs. reconfiguration splits; generate initial cost plans for financial model input |

| 2–6 | Prepare target cost plan and elemental breakdowns for cost control |

| 4–24 | Attend design meetings, update cost plans, issue reports, and align cashflows with financial modeling |

| 16–22 | Obtain input from trade contractors for major packages and price shell and external works |

| 20–24 | Finalize estimate and site overheads |

| 24–26 | Prepare and insert cost plans, drawings, and supporting materials into submission documents |

| Week 26 | Submit final bid |

This structured approach ensures that market testing, cashflow forecasting, and cost planning are synchronized with design progress, minimizing last-minute surprises.

Assigning Roles and Responsibilities

A submission of this magnitude requires clear leadership and delegated responsibility. The document advises appointing a presentation manager—a senior member responsible for managing the flow of information, deadlines, and deliverables across departments.

Responsibilities include:

- Confirming who is pricing each cost category (e.g., capital maintenance, decanting, lifecycle fund)

- Coordinating inputs for visual content (e.g., fly-through videos, artist impressions)

- Ensuring technical specifications and drawings align with the final cost plan

- Managing submission formatting, printing, and delivery logistics (sometimes requiring 30 to 40 physical copies)

By clarifying these roles from the beginning, the team avoids duplication, miscommunication, and version control issues.

Visual and Technical Content

PFI submissions often include:

- Drawings: Floor plans, elevations, site layouts

- Design Concepts: Diagrams and renderings that support design logic

- Fly-throughs or fly-pasts: Digital animations that offer a virtual tour of the future facility

- Specification Documents: Aligning materials and methods with cost assumptions

- Cost Workbook: A single spreadsheet containing elemental cost plans, risk, fees, inflation, and lifecycle assumptions

This blend of technical accuracy and visual clarity helps evaluation panels understand the bidder’s intent and confidence in delivery.

Digital and Physical Requirements

Although clients increasingly prefer digital submissions, the document notes that physical copies are still widely requested, sometimes reaching several hundred pages and multiple bound volumes.

To accommodate both formats:

- Use a consistent naming convention across files

- Validate hyperlinks and file integrity in digital versions

- Plan logistics for printing, binding, and delivery (ensuring reliable transport for what could amount to over a tonne of material)

This dual-format expectation underscores the need for early planning and internal quality control throughout the submission process.

Final Thoughts: Submitting More Than a Bid

In PFI procurement, the submission package is more than just a technical response—it is a reflection of the bidder’s organizational maturity, collaborative ability, and long-term thinking. A disorganized or rushed submission can raise concerns about a contractor’s capacity to handle a thirty-year concession.

Starting early, assigning ownership, maintaining consistency, and investing in clear visual and technical documentation can all significantly increase a bidder’s chances of success.

In a high-stakes environment where credibility and confidence win contracts, the submission document is the first proof that the bidder is ready—not just to build, but to partner.

Conclusion

Modern construction procurement is no longer about just awarding contracts—it’s about building long-term partnerships, aligning risk and responsibility, and ensuring infrastructure is designed, delivered, and maintained with maximum efficiency and value. From the evolution of procurement methods and client involvement to the complexities of risk profiles, cost estimation, and submission management, each element plays a vital role in shaping successful outcomes. As this guide shows, mastering procurement requires more than technical know-how—it demands strategy, foresight, and collaboration at every stage of the project lifecycle.